"Simply stunning ... An incredible achievement ... I have absolutely no doubt that [Queens of the Conquest] is going to be a dazzling success." (Dr Tracy Borman)

Daily Telegraph Book of the Year 2017

An Amazon October 2017 Best of the Month Category pick.

Listed among Entertainment Weekly’s “Best New Books".

One of Waterstones' Paperbacks of the Year, 2018.

Press release from Jonathan Cape:

ALISON WEIR LAUNCHES EPIC NEW MEDIEVAL SERIES

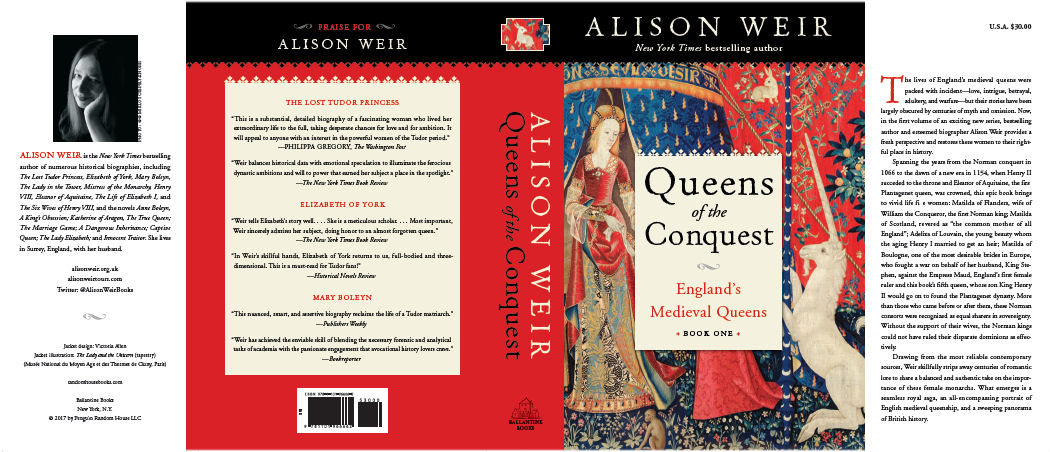

Bestselling historian Alison Weir is to launch an ambitious new series this autumn. ENGLAND'S MEDIEVAL QUEENS will explore the lives of England's queens over four centuries, from the Norman Conquest to the end of the Wars of the Roses.

The first in her new quartet of books, QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST, will be published in hardback, trade paperback and ebook on 28 September 2017.

In QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST, Weir strips away centuries of romantic mythology and prejudice to reveal the extraordinarily dramatic lives of the five queens of England in the century after the Norman Conquest. Beginning with Matilda of Flanders, who supported William the Conqueror in his invasion of England in 1066, and culminating in the turbulent life of the Empress Maud, who claimed to be queen of England in her own right and fought a bitter war to that end, the five Norman queens emerge as hugely influential figures and fascinating characters. QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST is a chronicle of love, murder, war and betrayal, filled with passion, intrigue and sorrow, peopled by a cast of heroines, villains, stateswomen and lovers.

The next three books in the series will cover the interconnected lives of England's queens in the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Alison Weir's earlier bestselling biographies, ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE and ISABELLA: SHE-WOLF OF FRANCE, QUEEN OF ENGLAND (both published by Vintage) will fit into the new series of books.

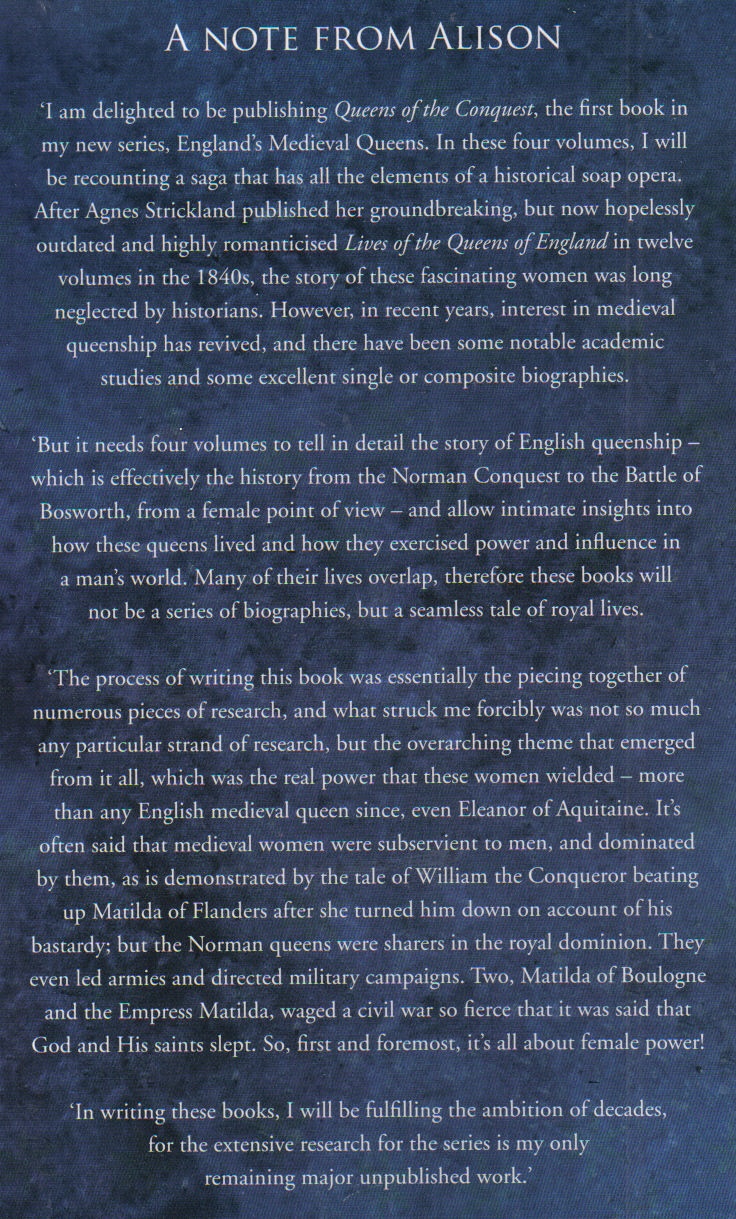

Alison Weir says: "I'm very excited about this new series. The story of England`s medieval queens has all the elements of a historical soap opera. After Agnes Strickland published her ground-breaking, but now hopelessly outdated and highly romanticised Lives of the Queens of England in twelve volumes in the 1840s, the story of England's medieval queens was long neglected by historians. In recent years, interest in medieval queenship has revived, and there have been some notable academic studies, and at least two excellent composite biographies. Yet it is impossible to tell this story fully in a single volume, and I should like to do that in these four books. In writing it, I will be fulfilling the ambition of decades, for the extensive research for the series is my only remaining major unpublished work."

Bea Hemming of Jonathan Cape, says: "Alison Weir's books have sold well over 1 million copies in the UK, making her without doubt one of Britain's most popular historians. We are delighted to continue to publish Alison, and to launch what promises to be her most ambitious project to date. It is hard to imagine anyone better qualified to chronicle the extraordinary lives of England's medieval queens, who for too long have been lost to the footnotes of history."

QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST has been selected as one of Waterstones' Paperbacks of the Year, 2018.

THE BOOKSELLER, 10th February 2017

NEW ALISON WEIR SERIES ON ENGLAND'S QUEENS

http://www.thebookseller.com/news/alison-weir-launches-new-series-lives-england-s-queens-486931

QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST, the first in the quartet, was launched at the Tower of London on 25th September 2017

EDITORIAL RECEPTION

"I really enjoyed all of it, but particularly loved the sections on Matilda & Stephen, and Maud. I have always had a rather tenuous grasp of this period and finally you have made me understand the people involved and the extraordinary times they lived through. Really does make Game of Thrones seem rather peaceful! I like the point you make (both in the opening sections and at the end)about the expectations people had of the behaviour of queens and highborn women. But it makes Matilda's achievements as a Queen, who really seems like an almost equal partner to her husband, all the more impressive. Great stuff and a wonderful launch for this series."

"Five of England's medieval queens come to life in the first volume of an epic series from bestselling author and historian Alison Weir. From Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror, to the Empress Matilda, mother to King Henry II, founder of the Plantagenet dynasty, Weir delivers a dramatic overview of the Norman period from a fresh new perspective."

REVIEWS

"I've just finished reading your chapters on Matilda, together with the introduction and preface. They are simply stunning. You bring her to life so vividly that it was like reading about her for the first time. I absolutely love it and can't wait to read the rest. I thought the introduction was just brilliant too - you really conjure up the atmosphere of early medieval England and set the context beautifully for the queens' stories. Huge, huge congratulations on an incredible achievement. I am already looking forward to the next three volumes!" (Tracy Borman)

"Reading the [book] has been a source of endless delight. This scholarly and highly readable account brings England's Norman queens out of the shadows and dazzlingly to life. Drawing on a wealth of fascinating contemporary sources, Alison Weir presents the drama, passion and intrigue of these extraordinary women's lives and restores them to their rightful place in history. A masterpiece. I would like to wish Alison every success with this stunning book. I am already looking forward to Volume II!" (Tracy Borman)

"Though Norman queens were largely unknowable, leave it to this prolific historical biographer to bring them to life. Having previously tackled the lives of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella of France, Weir presents five queens of the post-Norman Invasion era who sometimes wielded power in their own right, and not just as queen consort. As usual, Weir is meticulous in her research. Another sound feminist resurrection by a seasoned historian." (Kirkus Reviews)

"Another polished, fascinating gem from Weir, herself the queen of history writing. It was a man's world, but, as Weir convincingly shows, the fove queens wielded real power, in front of, as well as behind, the throne." (Sunday Express)

"Weir pens another readable, well-researched English history. Weir's research skills and storytelling ability combine beautifully to tell a fascinating story supported by excellent historical research. Fans of her fiction and non-fiction will enjoy this latest work." (Starred Library Journal review)

"I read your book, and I thought it was fantastic. You were able to turn these queens into complex characters of flesh and blood and put them in the context of their time without the men overwhelming their stories. They are so much stronger than I ever realized!" (Nancy Bilyeau)

“Weir skillfully strips away centuries of romantic lore to share a balanced and authentic take on the importance of these female monarchs.

What emerges is a seamless royal saga, an all-encompassing portrait of English medieval queenship, and a sweeping panorama of British his-

tory.” (Bookreporter)

"Weir brings her charaaracters vibrantly to life." (Must Reads, Daily Mail)

"The proclaimed expert on all things Tudor presents the drama, passion and intrigue of these extraordinary women's lives - it's a masterpiece."

(Waterstones' Picks)

"Alison Weir has the rare gift of being able to bring history vividly to life. This book... offers a fascinating perspective on a time of great change and uncertainty." (Choice magazine)

"A riveting history of the century following the Norman Conquest." (Paperback Pick of the Week, The Mail on Sunday)

"Underpinned by extensive reading in the original sources . . . [The book] will serve as a useful reference for those needing a detailed biographical compendium." (The Washington Post)

Alison Weir on QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST:

Writing the story of the Norman queens was essentially the piecing together of numerous pieces of research, and what struck me forcibly was not so much any particular strand of research, but the overarching theme that emerged from it all, which was the real power that these women wielded - more than any English medieval queen since, even Eleanor of Aquitaine. It's often said that medieval women were subservient in every way to men, but the Norman queens were sharers in the royal dominion. They even led armies and directed military campaigns. Two of them waged a civil war so fierce that it was said that God and His saints slept. I wrote my chapter on queenship before I wrote the main text - and I had to revise most of it later, in the light of what I had discovered. So, first and foremost, it's all about female power!

Several other things struck me while writing the book, and I'm rather proud of my research on the children of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders, because this is a subject long hotly debated by historians, who can rarely agree on the number of daughters, their dates, names and marriages, and indeed the dates of birth and order of arrival of all the children. I think I've come up with a credible overview.

Over the years, especially after I published Eleanor of Aquitaine, many people have asked if I would write a biography of Eleanor's mother-in-law, the Empress Maud (or Matilda), and I've now done so in Queens of the Conquest. Modern received wisdom is that she had a bad press among the chroniclers because she was a woman, that she was castigated for actions which would have been acceptable in a man, and that she deserves a better reputation. I thought this would be the outcome of my research, but it's not. So, although I think I have portrayed her fairly, my assessment of her is going to be controversial.

One strand of research enabled me to establish the history of the burials of Adeliza of Louvain, because it's rare to find an accurate account. I've also put forward theories that Adeliza and Matilda of Boulogne were much younger than is often suggested, and I did a lot of research on Matilda of Scotland's life in the nunneries of Romsey and Wilton, the chronology of which is often confused. The trajectory of events following the Pope's ban of the marriage of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders in 1049 is often recounted differently, but I believe the version in the book is the likeliest scenario. I have also debunked a lot of myths!

The book is about the five Norman queens. The names Matilda and Maud were then interchangeable (I won't give all othe other variants!), so for clarity, where their lives overlap, I have chosen to name them as follows: Matilda of Flanders, Matilda of Scotland, Adeliza of Louvain, Matilda of Boulogne and the Empress Maud.

FASCINATING FACTS

The Norman queens were sharers in the royal dominion. They exercised real power. They even led armies. Two of them waged a civil war so fierce that it was said that God and His saints slept.

From a beating by an offended suitor to an escape from a castle, camouflaged against the snow, theirs are colourful stories set in a turbulent age.

One Queen kept the mighty Conqueror faithful; another made the decision not to sleep with her husband; a third deserted hers and refused to use his title. On was married to a king who sired twenty-five bastards. Welcome to the age of feisty royal marriages.

Two of the queens in this book may have been as young as twelve when were married.

Of the ninety-three royal children born to fifteen of England's twenty medieval queens, twenty-seven died in childhood - nearly thirty percent.

Power, passion and piety - they all characterise the Norman queens, whose bounty and faith helped to construct a landscape of castles, abbey and churches that still stand today.

One Norman Queen loved an English noblemen, but he spurned her. It is said she did not forget it...

Another Queen had been veiled as a nun, then left her cloister to be marry a king.

Two queens defied their formidable husbands, one taking the part of her renegade son, the other of a saintly archbishop.

Two queens, by their marriages, united the royal Saxon line to that of the Norman conquerors.

One Queen wore a hair cloth under her royal habit, and trod the churches barefoot. She washed the feet of the diseased, handling their ulcers dripping with corruption, and kissed the sores of lepers.

The Norman queens set the standard for later medieval queenship in England, buttheir successors would rarely enjoy such authority and influence.

READ MORE ON QUEENS OF THE CONQUEST:

Tudor history Queen turns her gaze on medieval matriarchs

http://www.royalhistorygeeks.com/tudor-history-queen-turns-her-gaze-on-medieval-matriarchs/

BBC History Magazine: Norman England's Warrior Queen

https://www.scribd.com/article/358860451/Norman-England-S-Warrior-Queen

Alison Weir on Queens of the Conquest: England's Medieval Queens: interview with author Nancy Bilyeau

http://nancybilyeau.blogspot.co.uk/2017/11/interview-with-alison-weir-on-queens-of.html

History Extra: England's Norman queens and the power they wielded: an interview with Alison Weir

http://www.historyextra.com/article/norman/norman-queens-england-power-alison-weir-matilda

Quick Q&A with BBC History Magazine in advance of my event at the BBC History Weekend in York, November 2017

What can audiences look forward to in your talk?

A fast-paced account of the Norman queens of England, with new insights and an overview of Norman queenship that might surprise some.

Why are you so fascinated by this topic?

I've always been fascinated by women's histories, especially those of royal women, who lived such rarefied, ritualised lives; and I love piecing together fragments of research to see what emerges - such being the nature of medieval biography.

Tell us something that might surprise or shock us about this area of history.

The power that queens wielded in this brutal, male-dominated world.

What is the hardest question you’ve ever been asked about your area of expertise?

When I was giving a talk on Eleanor of Aquitaine, someone asked me if I could expound on the education of Hildegarde of Bingen. The answer was, er, actually, no!

If you could go back in time to meet one historical figure, who would you choose and why? AND/OR If you could go back in time to witness one moment in history, what would you choose and why?

I would like to meet Anne Boleyn (who wouldn't?), and ask her how she really felt about Henry VIII, and what was the truth behind her fall.

What historical mystery would you most like to solve?

That of the Princes in the Tower. Most of the evidence points to Richard III being responsible, but I'd love to see something that left no room for doubt either way.

What job do you think you would be doing now if you weren’t a historian/author?

I'd run my historical tours full-time. Or I'd be a lady of leisure!

HOW THE STORY BEGINS...

"He is little, but he will grow," said Robert the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy, of his bastard son, who, as a child of seven, was being left to govern the duchy during his father's absence. But shortly afterwards, while on a pilgrimage in Bithynia, Robert died, and since he left no legitimate heirs, the child William succeeded him as duke.

William's childhood was turbulent. Many Norman lords resented a bastard wearing the ducal crown. The boy's guardians were murdered, and there were attempts on his life. But the young Duke survived to grow into a man to be reckoned with, and with him grew his legend. 'He was mild to the good men that loved God, and beyond all measure severe to the men that gainsaid his will.' At Val-ès-Dunes, William proved his skill as a soldier, and thenceforth his reputation spread. 'To see him reigning in his horse, shining with sword, helmet and shield, and brandishing his lance was a pleasant yet terrible sight,' wrote a contemporary. Every battle William fought he won. Throughout Normandy, he came to be greatly respected and admired - but never loved.

The taint of his birth haunted William all his life. His mother, Herleva of Falaise, had probably been a tanner's daughter. Her son defiantly signed his letters 'William Bastard', but no other person was permitted to remind him of his illicit birth. After the besieged inhabitants of Alençon hung tanned hides over the walls, mocking the Duke, he meted out a grim revenge, ordering the hands and feet of those who had jeered to be cut off, himself standing by to see it done. Yet to those who were obedient and loyal, he was just and merciful.

It was probably in 1050 that William married Matilda, daughter of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders. In an age when women were expected to be submissive, Matilda was an able and spirited politician, and it was said that she at first flatly refused to marry William because he was a bastard. An outraged William allegedly rode swiftly to Lille or Bruges, where he sought out Matilda and administered a harsh beating. Evidently impressed, she agreed to be his wife, saying, 'He must be a man of great courage and high daring who could venture to come and beat me in my own father's palace.'

William was known to be a stark, upright man, a man of principle. Ostentatiously pious on the surface, he did not, however, desist when the Pope forbade his marriage on grounds that remain obscure. It was nine years before he was able to persuade the Pope to grant a dispensation, and as penance both he and Matilda founded abbeys at Caen: William's was the Abbey of St Stephen, Matilda's the Abbey of the Trinity, known as the Abbaye aux Dames. Later, they would be buried in their respective abbey churches, although William's tomb was destroyed during the French Revolution.

It is often said that the Duchess Matilda was little more than four feet tall, but forensic evidence has disproved that. For a few years, she was preoccupied with bearing children, and there is evidence to suggest that their marriage was a satisfying, if not loving, partnership.

Legend had it that, when she was pregnant with him, William's mother had a dream in which she saw a tree growing out of her body, and the branches of the tree stretched out over Normandy and England. In 1051, William may have visited England, where his cousin Edward the Confessor was king. Although married, the saintly Edward had taken a vow of chastity, and was therefore childless. William later claimed that Edward had promised him the succession to the crown of England.

But there was another contender for the English crown, the powerful Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, whose sister was Edward's wife. Here, fate played into William's hands. In 1064, Harold was shipwrecked on the Norman coast. William would not allow him to return to England until he had sworn on holy relics to do everything in his power to help the Duke to secure the English throne when the time came.

But when Edward died on 5 January, 1066, Harold seized the crown, claiming he was the King's chosen successor. An enraged William resolved to take England by force. By September, he had assembled a mighty fleet and a great army, and that month he set sail in his flagship, the Mora, which was a gift from his wife.

When the Normans landed at Pevensey, Harold was with his army in the north, resisting an invasion by King Harold Hardrada of Norway. After defeating and killing Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, he marched south to deal with the Norman invaders. The two armies met on 14 October, at Senlac Hill, a few miles from Hastings, and a fierce battle ensued, which lasted all day. Harold and his men was drawn up on the crest of Senlac Hill, which placed the Normans below at a disadvantage, but when the Normans retreated, the English abandoned their strong position and raced after them, at which point the tide turned in William's favour. Harold fell, mortally wounded, beneath his standards depicting the Fighting Man and the Gold Dragon of Wessex. Shortly afterwards, William marched on London and proclaimed himself king.

On Christmas Day, he was crowned in the newly-built Westminster Abbey, but there was resistance to his rule and the conquest continued. In 1068, he deemed southern England sufficiently subdued to send for Matilda and have her crowned queen. It is a myth that she was the first crowned queen of England.

By 1071, after William had laid waste the north, which had long resisted his rule, the Norman Conguest was complete. Feudalism was established in England, the Church was reformed along strict Norman lines, and the administration overhauled; in 1086, the Domesday survey was carried out, and details of all the land-holdings in the kingdom were recorded. Around the same time, the Tower of London was built, as were many other castles, not only for defence, but to keep the King's subjects in order and establish local administrative centres.

William's rule was harsh but effective. He abolished capital punishment but replaced it with castration and mutilation. After his death, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded: 'We must not forget the good order he kept in the land, so that a man of any substance could travel unmolested throughout the country with his bosom full of gold. No man dared to slay another." Nevertheless, 'A hard man was the King.' ;

William and Matilda had four sons and probably six daughters. The eldest son, Robert, was a disappointment to his father, who nicknamed him Curthose because of his short legs. When William was in England, Robert was left as co-regent with his mother in Normandy. The young prince was ambitious and land hungry, but when he grew older and still his father did not allow him any real responsibilty, he ventured to suggest that he might be invested with the dukedom of Normandy.

William was furious. 'It is not my custom to strip till I go to bed,' he thundered, 'and as long as I live, I will not deprive myself of my native realm, neither will I divide it with another, for it is written, Every kingdom that is divided against itself shall become desolate. It is not to be borne that he who owes his existence to me should aspire to be my rival in mine own dominions.'

When Robert threatened to leave Normandy and seek justice from strangers, William ordered him to go at once, but behind her husband's back, Queen Matilda, who is said to have loved Robert above her other children, pawned her jewels in order to give him some money. Inevitably, William found out.

The second son, Richard, was said to be the one most like him in appearance. He and his brothers were tutored by the great Archbishop Lanfranc. Unfortunately, Richard's story ended in tragedy.

The King's third son, another William, was Rufus, probably because of his red hair and his violent temper.

Two of William's daughters, Adeliza and Cecilia, were dedicated to the Church in youth. The youngest, Adela, married the Count of Blois and became the mother of the future King Stephen of England. One of the daughters was betrothed at one

time to Harold, Earl of Wessex.

William was a faithful husband. Tales that he had mistresses are probably baseless. One claims that the Queen discovered an illicit liaison and, in a fit of jealousy, had the young woman hamstrung.

In 1087, William turned sixty. He was now a fat and irascible old man, but by no means willing to give up the struggle to retain hold of what was his. While besieging Mantes, he fell from his horse on to hot rubble, sustaining mortal injuries. Nearing his end, he murmured, "I commend myself to that blessed Lady Mary, the Mother of God, that She by her holy intercession may reconcile me to her most dear son, our Lord Jesus Christ." As his body was being lowered into the tomb, the gases caused by decomposition caused it to burst open, and a terrible smell filled the church. The funeral rites were hurriedly concluded and the huge congregation fled. A great, all-powerful king, observed the chronicler Orderic Vitalis, was reduced to nothing by such indignities.

He was surnamed Conqueror, not because of the battles he won, but because of the amount of territory he acquired. For Conqueror at that time meant purchaser or acquirer. Certainly it was better than Bastard.

The image said to be of Matilda of Scotland's seal in the book is actually that of the Empress Maud's seal. This is Matilda of Scotland's seal.

MISCELLANY

I am grateful to the reader who pointed out that Charlemagne was crowned in Rome, not in Aachen. Apologies fot the error!